💡 What You Need to Know Right Away

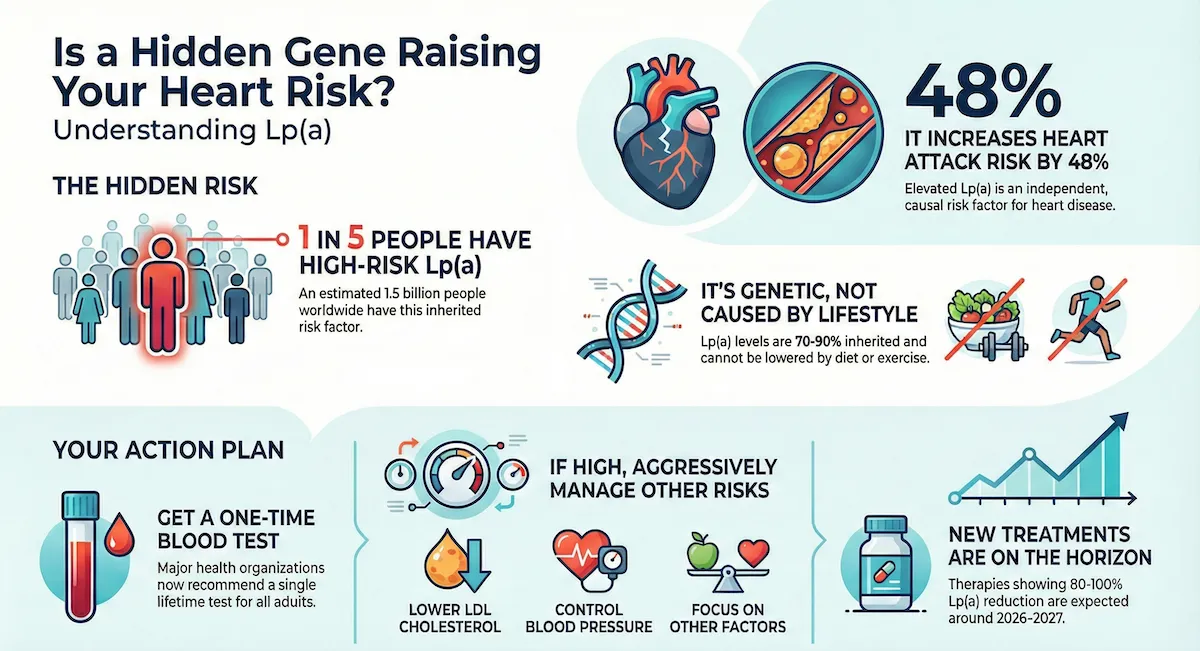

- 1 in 5 people have elevated Lp(a) levels that increase heart disease risk, yet most have never been tested.[Evidence: C][2]

- High Lp(a) (≥50 mg/dL) increases heart attack risk by 48% (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.32-1.67), consistently across all ethnic groups.[Evidence: B][8]

- Lp(a) is 70-90% genetically determined. Diet and exercise cannot lower it, making a one-time test sufficient for most people.[Evidence: A][4]

- Elevated Lp(a) doubles the risk of premature cardiovascular disease (OR 2.15), with even higher risk in South Asian populations (OR 3.71).[Evidence: A][10]

You may have never heard of Lp(a), but this inherited cholesterol particle could be silently increasing your heart disease risk. An estimated 1.5 billion people worldwide have elevated Lp(a) levels.[Evidence: A][4] Yet despite being an independent, causal risk factor for cardiovascular disease, most people have never been tested.

2024 marked a turning point for Lp(a) awareness. The National Lipid Association issued its first clinical endorsement for universal screening, and testing rates increased dramatically. Five promising therapies showing 80-100% Lp(a) reduction entered advanced clinical trials, with results expected in 2025-2026.

This guide explains what an Lp(a) test measures, who should get tested, how to interpret your results, and what treatment options exist. Whether you have a family history of early heart disease or simply want to understand your complete cardiovascular risk, this article provides the evidence-based information you need.

❓ Quick Answers

What is a lipoprotein(a) test?

An Lp(a) test is a blood test that measures lipoprotein(a), a type of cholesterol particle linked to heart disease. Unlike regular LDL cholesterol, Lp(a) levels are over 90% genetically determined and cannot be changed by diet or exercise.[Evidence: C][2] The test requires a simple blood draw and results are typically available within 3-7 days.

What is a normal Lp(a) level?

According to the 2024 National Lipid Association guidelines, Lp(a) below 75 nmol/L (approximately 30 mg/dL) is considered low risk. Levels between 75-125 nmol/L indicate intermediate risk, while levels at or above 125 nmol/L (approximately 50 mg/dL) indicate high cardiovascular risk requiring clinical attention.[Evidence: D][6]

Do you need to fast for an Lp(a) test?

Fasting is generally not required for a standalone Lp(a) test because Lp(a) levels remain stable regardless of recent food intake. However, if your doctor orders Lp(a) along with a standard lipid panel (which includes triglycerides), you may need to fast for 9-12 hours. Always confirm with your testing facility.

Who should get an Lp(a) test?

The European Atherosclerosis Society recommends universal Lp(a) screening once in every adult's lifetime.[Evidence: D][3] Priority testing is recommended for people with family history of early heart disease (men under 55, women under 65), personal history of heart attack or stroke, LDL cholesterol above 190 mg/dL, or a family member with elevated Lp(a).

How much does an Lp(a) test cost?

Without insurance, an Lp(a) test typically costs $30-$100. National laboratories like Labcorp and Quest offer testing for $60-80, while direct-to-consumer options range from $50-75. Note that Medicare and many insurance plans do not yet cover Lp(a) testing as of 2025, though coverage is expanding as new treatments emerge.

Is high Lp(a) genetic?

Yes. Lp(a) is 70-90% genetically determined, making it the most heritable of all lipoproteins.[Evidence: A][4] If one parent has elevated Lp(a), each child has a 50% chance of inheriting it. This is why cascade family testing is recommended when someone is diagnosed with high Lp(a).[Evidence: D][3]

What happens if my Lp(a) is high?

If your Lp(a) is elevated (≥125 nmol/L or ≥50 mg/dL), your doctor will focus on aggressively managing other cardiovascular risk factors you can control: LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, blood sugar, smoking, and weight. For very high levels, lipoprotein apheresis (a blood-filtering procedure) is FDA-approved.[Evidence: D][3] New RNA-based therapies showing 80-100% reduction are expected to reach the market in 2026-2027.

🔬 How Does Lp(a) Cause Heart Disease?

Understanding why Lp(a) damages your arteries helps explain why this test matters. Think of Lp(a) as LDL cholesterol's more dangerous cousin. It carries the same cholesterol cargo, but with an extra "sticky" protein called apolipoprotein(a) attached. This makes Lp(a) particles act like velcro in your arteries, clinging to vessel walls and accelerating plaque buildup.

Imagine your arteries as highways. Regular LDL particles are like cars passing through. Lp(a) particles, however, are cars with grappling hooks. They latch onto the highway surface, causing traffic jams (plaque) that restrict blood flow. Research shows Lp(a) particles are approximately 6 times more likely to lodge in artery walls compared to regular LDL particles of the same size.

The cardiovascular damage from elevated Lp(a) is well-documented across multiple outcomes:

- Heart attack risk: Lp(a) ≥50 mg/dL increases myocardial infarction risk by 48% (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.32-1.67), consistent across 7 ethnic groups studied.[Evidence: B][8]

- Premature cardiovascular disease: Elevated Lp(a) more than doubles the risk of early-onset heart disease (OR 2.15), with 51 studies involving 100,540 participants confirming this association.[Evidence: A][10]

- Long-term outcomes: In a 21.1-year follow-up study of 27,756 individuals, those with Lp(a) at or above the 90th percentile had a 46% higher risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (HR 1.46). The risk was even higher in diabetic patients (HR 1.92).[Evidence: A][1]

- Major adverse cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis of 562,301 participants found elevated Lp(a) increased MACE risk by 26-33% regardless of inflammation status (HR 1.26-1.33).[Evidence: A][9]

- Aortic valve disease: Those in the highest Lp(a) tertile experience 41% faster progression of aortic stenosis (narrowing of the heart valve).[Evidence: A][11]

- Post-intervention outcomes: Among 45,059 patients who underwent coronary stent procedures (PCI), elevated Lp(a) increased the risk of subsequent major cardiac events by 38% (RR 1.38), cardiovascular death by 58% (RR 1.58), and repeat heart attacks by 44% (RR 1.44).[Evidence: A][12]

- Subclinical disease: Elevated Lp(a) is associated with coronary artery calcification even in people without symptoms, based on analysis of over 34,000 asymptomatic individuals.[Evidence: A][15]

- Premature coronary artery disease: Lp(a) levels are significantly higher in patients who develop coronary artery disease at a young age compared to age-matched controls.[Evidence: A][16]

The risk varies by ancestry. South Asian populations face the highest risk from elevated Lp(a), with an odds ratio of 3.71 for premature cardiovascular disease, compared to an overall OR of 2.15.[Evidence: A][10]

📊 Understanding Your Lp(a) Test Results

Interpreting your Lp(a) results requires understanding the measurement units and risk thresholds. Laboratories report Lp(a) in two different units: mass units (mg/dL) and molar units (nmol/L). These units do not convert precisely due to the variable size of Lp(a) particles.

| Risk Level | mg/dL | nmol/L | Clinical Significance | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal | <14 | <35 | Baseline cardiovascular risk | [D][6] |

| Borderline | 14-30 | 35-75 | Low additional risk (~10-20%) | [D][6] |

| Intermediate | 31-49 | 76-124 | Moderate additional risk (~30-50%) | [D][6] |

| High Risk | ≥50 | ≥125 | 48% increased MI risk (HR 1.46-1.48) | [A][1][8] |

| Very High Risk | ≥180 | ≥430 | 3-4x increased CVD risk, apheresis consideration | [D][3] |

Important considerations when interpreting results:

- Sex differences: Women show approximately 27% higher Lp(a) levels after menopause compared to before menopause. Risk associations become similar between sexes after age 50.[Evidence: B][7]

- Stability: Lp(a) levels remain stable throughout adult life after age 5, so one measurement is typically sufficient.

- Unit confusion: Always note whether your result is in mg/dL or nmol/L. The high-risk threshold is ≥50 mg/dL OR ≥125 nmol/L (not interchangeable numbers).

⚠️ Test Limitations and Important Warnings

Measurement Standardization Challenges

Lp(a) measurement faces unique technical challenges. The apolipoprotein(a) portion of Lp(a) contains a variable number of repeating protein units called kringle IV type 2 (KIV-2) repeats. This means Lp(a) particles vary in size between individuals, which affects how accurately different laboratory methods can measure them.

The World Health Organization and International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) have developed a standard reference material (SRM-2B) to improve consistency between laboratories. The 2024 NLA guidelines and 2019 ESC guidelines both prefer reporting in molar units (nmol/L) because this measurement is less affected by particle size variation.

Factors That May Temporarily Affect Results

- Acute illness or inflammation: May temporarily elevate Lp(a) levels

- Kidney disease: Can increase Lp(a) levels

- Liver disease: May decrease Lp(a) production

- Pregnancy and menopause: Hormonal changes can affect levels

- Certain medications: Estrogen therapy and niacin may modestly reduce Lp(a); report all medications to your doctor

Test Procedure Risks

The Lp(a) test requires a standard blood draw (venipuncture). Risks are minimal and include:

- Bruising at puncture site (10-20% of blood draws)

- Hematoma (2-5%)

- Lightheadedness or fainting (1-3%)

🥗 Who Should Get Tested for Lp(a)

The European Atherosclerosis Society recommends that every adult should have their Lp(a) measured at least once in their lifetime.[Evidence: D][3] The 2024 National Lipid Association guidelines endorse universal screening for all adults.[Evidence: D][6]

Priority Testing Recommended For:

- Family history of early heart disease: Heart attack or stroke in male relatives under 55 or female relatives under 65

- Personal history of cardiovascular disease: Prior heart attack, stroke, or peripheral artery disease

- High LDL cholesterol: LDL ≥190 mg/dL, especially if not responding fully to statin therapy

- Familial hypercholesterolemia: Approximately 30% of FH patients also have elevated Lp(a)

- Family member with elevated Lp(a): 50% inheritance probability

- Recurrent cardiovascular events: Despite optimal treatment of other risk factors

- Aortic valve disease: Calcific aortic stenosis, especially if progressing

Cascade Family Screening

If you are diagnosed with elevated Lp(a), your first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, children) should also be tested. Research shows cascade screening identifies 1 elevated case for every 2 relatives screened (NNS 1.3-2.9), making it highly efficient.[Evidence: C][5]

Cascade screening is superior to opportunistic screening in the general population, where the number needed to screen to find one elevated case is approximately 6.[Evidence: C][5]

How to Get Tested

- Ask your doctor: Request an Lp(a) test specifically. It is not included in routine cholesterol panels.

- Direct-to-consumer options: Labcorp OnDemand, Quest Direct, and other services allow ordering without a prescription ($50-100).

- Insurance pre-authorization: If you have risk factors, ask your doctor to document medical necessity for potential coverage.

What To Do If Your Lp(a) Is High

Since Lp(a) cannot currently be lowered with medication or lifestyle changes, the focus is on:

- Aggressively lowering LDL cholesterol (target often <70 mg/dL or <55 mg/dL)

- Optimizing blood pressure control

- Managing blood sugar if diabetic

- Smoking cessation

- Maintaining healthy weight

- Discussing aspirin therapy with your doctor

- For very high levels (≥180 mg/dL): Discussing lipoprotein apheresis, an FDA-approved blood-filtering procedure[Evidence: D][3]

⚖️ Lp(a) vs. LDL Cholesterol: Key Differences

Both Lp(a) and LDL are cholesterol-carrying particles, but they differ in critical ways that affect testing, treatment, and risk management.

| Feature | Lp(a) | LDL Cholesterol |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic determination | 70-90% inherited[4] | 30-40% inherited |

| Modified by diet | No | Yes (10-15% reduction possible) |

| Modified by exercise | No | Yes (modest improvements) |

| Lowered by statins | No (may slightly increase) | Yes (30-50% reduction) |

| Atherogenicity per particle | ~6x higher | Reference (1x) |

| Testing frequency | Once in lifetime (levels stable) | Every 4-6 years (or annually if elevated) |

| Included in standard panel | No (must request separately) | Yes |

| Prevalence of high levels | ~20% of population[2] | ~40% of adults |

| FDA-approved treatments | Lipoprotein apheresis only | Multiple (statins, ezetimibe, PCSK9i) |

| Test cost without insurance | $30-100 | $10-30 |

Important: Lp(a) and LDL are independent risk factors. Having high Lp(a) increases cardiovascular risk even if your LDL is well-controlled, and vice versa. This is why both should be measured for a complete risk assessment.

What The Evidence Shows (And Doesn't Show)

What Research Suggests

- Elevated Lp(a) is an independent, causal risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, supported by genetic studies, prospective cohorts, and Mendelian randomization analyses.[Evidence: A][4]

- High Lp(a) (≥50 mg/dL or ≥125 nmol/L) increases heart attack risk by 46-48% (HR 1.46, OR 1.48), consistently observed across 7 ethnic groups and over 21 years of follow-up.[Evidence: A][1][Evidence: B][8]

- Elevated Lp(a) more than doubles the risk of premature cardiovascular disease (OR 2.15, based on 51 studies with 100,540 participants).[Evidence: A][10]

- Approximately 1 in 5 people (20-30%) have elevated Lp(a), representing 1.5 billion people worldwide.[Evidence: A][4]

- Lp(a) is 70-90% genetically determined, making lifestyle modification ineffective for lowering levels.[Evidence: A][4]

What's NOT Yet Proven

- Cardiovascular outcome reduction: No clinical trial has yet proven that lowering Lp(a) reduces heart attacks or strokes. The RNA therapy outcome trials (OCEAN(a)-Outcomes, Lp(a)HORIZON) will report results in 2025-2026.

- Optimal treatment thresholds: While risk stratification thresholds exist (≥125 nmol/L high risk), the level at which treatment should begin remains undetermined pending medication availability.

- Cost-effectiveness: Whether universal Lp(a) screening is cost-effective compared to targeted screening has not been definitively established.

- Pediatric screening: Optimal age to begin screening (some suggest with first lipid panel in young adulthood) is not established by clinical trial evidence.

- Precise unit conversion: Due to apolipoprotein(a) size variation, exact conversion between mg/dL and nmol/L is not possible.

Where Caution Is Needed

- Treatment expectations: Currently, no FDA-approved medication lowers Lp(a). Patients may feel frustrated knowing their risk without having treatment options. Counseling should emphasize aggressive management of modifiable risk factors.

- Test result variability: Results may vary between laboratories due to measurement standardization challenges. Use the same laboratory for any follow-up testing.

- Insurance barriers: Many patients discover Medicare and private insurance do not cover testing after the fact. Verify coverage or budget for out-of-pocket costs ($30-100) before ordering.

- Psychological impact: Learning about an inherited, unmodifiable risk factor may cause anxiety. Emphasize that knowing enables more aggressive prevention and that treatments are on the horizon.

- Over-interpretation: Lp(a) is one of many cardiovascular risk factors. A high level does not guarantee disease, and a low level does not guarantee protection.

Should YOU Get Tested?

Best suited for: All adults should consider testing once in their lifetime, per international guidelines.[Evidence: D][3][6] Priority testing for those with family history of early heart disease, personal cardiovascular disease history, high LDL cholesterol (≥190 mg/dL), familial hypercholesterolemia, or family members with elevated Lp(a).

Not recommended for: No absolute contraindications to testing exist. Those who may find test results psychologically distressing without actionable options should discuss with their healthcare provider first.

Realistic timeline: Results available in 3-7 days. Single lifetime measurement is typically sufficient. If elevated, focus shifts to optimizing other cardiovascular risk factors while awaiting new treatments (expected 2026-2027).

When to consult a professional: Discuss results with a cardiologist or lipid specialist if Lp(a) is elevated, especially if combined with other cardiovascular risk factors or personal/family history of heart disease.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does insurance cover Lp(a) testing?

Coverage varies significantly. As of 2025, Medicare does not cover Lp(a) testing based on outdated 2009 USPSTF guidelines. Many private insurers also deny coverage, though this is changing as clinical guidelines increasingly recommend universal screening. Some plans cover testing with documented medical necessity (family history of early CVD, familial hypercholesterolemia, elevated LDL). Direct-to-consumer testing through Labcorp OnDemand or Quest Direct costs $50-75 without insurance. Contact your insurance provider before testing and ask your doctor to document risk factors that may support coverage.

How do you lower high Lp(a)?

Currently, no FDA-approved medications specifically target Lp(a). Diet, exercise, and statins do not lower Lp(a) levels. The only FDA-approved option for very high levels (typically ≥180 mg/dL or ≥430 nmol/L) is lipoprotein apheresis, a procedure that filters Lp(a) from the blood every 1-2 weeks. However, multiple RNA-based therapies are in advanced clinical trials showing 80-100% Lp(a) reduction. Olpasiran demonstrated significant Lp(a) lowering with correlated reduction in harmful oxidized phospholipids (r = 0.79). Muvalaplin, an oral medication, reduced Lp(a) by up to 65% in phase 2 trials. These therapies are expected to receive FDA approval in 2026-2027.

What is the difference between Lp(a) and LDL cholesterol?

Lp(a) and LDL are both lipoproteins that carry cholesterol in your blood, but Lp(a) has an extra protein (apolipoprotein(a)) that makes it stickier and more dangerous. While LDL responds to diet changes and statin medications, Lp(a) is 70-90% genetically determined and unaffected by lifestyle or most medications. Particle for particle, Lp(a) is approximately 6 times more likely to cause artery blockage than LDL. Standard cholesterol tests measure LDL but not Lp(a), so you must request the Lp(a) test separately. Both are independent risk factors, so optimal cardiovascular risk management requires measuring both.

Can diet and exercise lower Lp(a)?

No. Unlike LDL cholesterol, Lp(a) levels cannot be meaningfully lowered through diet, exercise, or other lifestyle modifications. This is because Lp(a) levels are 70-90% determined by genetics, specifically by variants in the LPA gene that controls apolipoprotein(a) production. Some studies have shown very modest effects from certain dietary changes, but these are not clinically significant. If your Lp(a) is elevated, focus on controlling the cardiovascular risk factors you can modify: LDL cholesterol, blood pressure, blood sugar, weight, and smoking status.

How often should Lp(a) be tested?

For most people, a single Lp(a) measurement is sufficient because levels remain stable throughout adult life after approximately age 5. This is because Lp(a) is genetically determined and not affected by diet or lifestyle. Repeat testing may be considered in specific circumstances: after starting niacin or estrogen therapy (which may modestly lower Lp(a)), during pregnancy or menopause (hormonal effects), or if the initial test was performed during acute illness or inflammation (which can temporarily elevate levels). The European Atherosclerosis Society recommends universal screening once in every adult's lifetime.

Are there new treatments for high Lp(a)?

Yes, multiple promising therapies are in late-stage clinical trials. RNA-based drugs that silence the LPA gene show remarkable efficacy: olpasiran, pelacarsen, lepodisiran, and zerlasiran all demonstrate 80-100% Lp(a) reduction in trials. Olpasiran phase 2 data shows Lp(a) lowering correlates with reduction in harmful oxidized phospholipids. The first oral option, muvalaplin, reduced Lp(a) by up to 65% in a phase 2 trial published in JAMA. Phase 3 cardiovascular outcome trials are underway with results expected in 2025-2026 and potential FDA approvals in 2026-2027. This represents the first time in history that specific Lp(a)-lowering therapy is on the horizon.

How accurate is the Lp(a) test?

Lp(a) testing accuracy is good but faces unique standardization challenges. The apolipoprotein(a) protein varies in size between individuals due to different numbers of repeating structural units (kringle IV type 2 repeats). This size variation affects how different laboratory methods measure Lp(a). Molar units (nmol/L) are preferred over mass units (mg/dL) because they are less affected by this variation. The WHO/IFCC has developed standard reference materials to improve consistency between laboratories. For clinical decision-making, the test reliably stratifies patients into risk categories, but comparing results between different laboratories or over time may show some variation. Always use the same laboratory for follow-up testing.

What is considered dangerously high Lp(a)?

Lp(a) levels at or above 50 mg/dL (≥125 nmol/L) are considered high risk, associated with a 46-48% increased risk of cardiovascular events. Very high levels at or above 180 mg/dL (≥430 nmol/L) are associated with 3-4 times increased cardiovascular risk and may qualify for lipoprotein apheresis treatment. In patients with elevated Lp(a), the risk is magnified by other factors: diabetic patients with high Lp(a) have a 92% increased risk (HR 1.92). The risk is also higher in certain populations, with South Asians showing an odds ratio of 3.71 for premature cardiovascular disease.

How does Lp(a) cause heart disease?

Lp(a) promotes cardiovascular disease through multiple mechanisms. First, like LDL, it delivers cholesterol into artery walls, contributing to plaque formation. Second, the apolipoprotein(a) component carries oxidized phospholipids that trigger inflammation and damage to vessel walls. Third, apolipoprotein(a) structurally resembles plasminogen (a clot-dissolving protein) and may interfere with the body's ability to break down blood clots, increasing thrombosis risk. This combination of cholesterol delivery, inflammation, and clot promotion makes Lp(a) particles approximately 6 times more atherogenic than regular LDL particles. The result is accelerated atherosclerosis, with high Lp(a) associated with 41% faster progression of aortic valve disease and more than double the risk of premature cardiovascular events.

Can Lp(a) levels change over time?

Lp(a) levels are remarkably stable throughout adult life because they are genetically determined. After approximately age 5, levels remain constant regardless of diet, exercise, or most medications. However, several factors can cause temporary or modest changes: acute illness or inflammation can temporarily raise levels; kidney disease increases Lp(a); liver disease may decrease production; menopause raises levels by approximately 27% in women; estrogen therapy and high-dose niacin can modestly reduce levels. The new RNA-based therapies in clinical trials represent the first interventions capable of dramatically lowering Lp(a) (80-100% reduction), which may change the treatment landscape when approved.

Our Accuracy Commitment and Editorial Principles

At Biochron, we take health information seriously. Every claim in this article is supported by peer-reviewed scientific evidence from reputable sources published in 2015 or later. We use a rigorous evidence-grading system to help you understand the strength of research behind each statement:

- [Evidence: A] = Systematic review or meta-analysis (strongest evidence)

- [Evidence: B] = Randomized controlled trial (RCT)

- [Evidence: C] = Cohort or case-control study

- [Evidence: D] = Expert opinion or clinical guideline

Our editorial team follows strict guidelines: we never exaggerate health claims, we clearly distinguish between correlation and causation, we update content regularly as new research emerges, and we transparently note when evidence is limited or conflicting. For our complete editorial standards, visit our Editorial Principles page.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult qualified healthcare professionals before making changes to your health regimen, especially if you have medical conditions or take medications.

References

- 1 . Lipoprotein(a) and Long-Term Cardiovascular Risk in a Multi-Ethnic Pooled Prospective Cohort. Wong ND, Fan W, Hu X, et al. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2024; 83(16):1511-1525. PubMed [Evidence: A]

- 2 . Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease. Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A. Lancet, 2024; 404(10459):1255-1264. PubMed [Evidence: C]

- 3 . Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, et al. European Heart Journal, 2022; 43(39):3925-3946. PubMed [Evidence: D]

- 4 . 2024: The year in cardiovascular disease - the year of lipoprotein(a). Research advances and new findings. Sosnowska B, Toth PP, Razavi AC, et al. Archives of Medical Science, 2025; 21(2):355-373. PubMed [Evidence: A]

- 5 . Effectiveness of cascade screening for elevated lipoprotein(a), an underdiagnosed family disorder. Annink ME, Janssen ES, Reeskamp LF. Current Opinion in Lipidology, 2024; 35(6):290-296. PubMed [Evidence: C]

- 6 . A focused update to the 2019 NLA scientific statement on use of lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice. Koschinsky ML, Bajaj A, Boffa MB, et al. Journal of Clinical Lipidology, 2024; 18(3):e308-e319. PubMed [Evidence: D]

- 7 . Sex differences of lipoprotein(a) levels and associated risk of morbidity and mortality by age: The Copenhagen General Population Study. Simony SB, Mortensen MB, Langsted A, et al. Atherosclerosis, 2022; 355:76-82. PubMed [Evidence: B]

- 8 . Lipoprotein(a) Levels and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction Among 7 Ethnic Groups. Paré G, Çaku A, McQueen M, et al. (INTERHEART Investigators). Circulation, 2019; 139(12):1472-1482. PubMed [Evidence: B]

- 9 . Association of Lipoprotein(a) With Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Across hs-CRP: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Alebna PL, Han CY, Ambrosio M, et al. JACC Advances, 2024; 3(12):101409. PubMed [Evidence: A]

- 10 . Association between lipoprotein(a) and premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tian X, Zhang N, Tse G, et al. European Heart Journal Open, 2024; 4(3):oeae031. PubMed [Evidence: A]

- 11 . Lipoprotein(a) and Calcific Aortic Valve Stenosis Progression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arsenault BJ, Loganath K, Girard A, et al. JAMA Cardiology, 2024; 9(9):835-842. PubMed [Evidence: A]

- 12 . Impact of Elevated Lipoprotein A on Clinical Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sinha T, Guntha M, Mayow AH, et al. Cureus, 2024; 16(5):e61069. PubMed [Evidence: A]

- 13 . Olpasiran, Oxidized Phospholipids, and Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers: Results From the OCEAN(a)-DOSE Trial. Rosenson RS, López JAG, Gaudet D, et al. JAMA Cardiology, 2025; 10(5):482-486. PubMed [Evidence: B]

- 14 . Oral Muvalaplin for Lowering of Lipoprotein(a): A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nicholls SJ, Ni W, Rhodes GM, et al. JAMA, 2025; 333(3):222-231. PubMed [Evidence: B]

- 15 . Predictive value of lipoprotein(a) in coronary artery calcification among asymptomatic cardiovascular disease subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vazirian F, Sadeghi M, Kelesidis T, et al. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases, 2023; 33(11):2055-2066. PubMed [Evidence: A]

- 16 . Lipoprotein(a) is associated with premature coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Papathanasiou KA, Kazantzis D, Rallidis LS. Coronary Artery Disease, 2023; 34(4):227-235. PubMed [Evidence: A]

Medical Disclaimer

This content is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide medical advice or to take the place of such advice or treatment from a personal physician. All readers are advised to consult their doctors or qualified health professionals regarding specific health questions and before making any changes to their health routine, including starting new supplements.

Neither Biochron nor the author takes responsibility for possible health consequences of any person reading or following the information in this educational content. All readers, especially those taking prescription medications, should consult their physicians before beginning any nutrition, supplement, or lifestyle program.

If you have a medical emergency, call your doctor or emergency services immediately.